United Mafias of Europe: what is lacking to fight crime in EU Interactive Map: the presence of clans in each Member State

Project coordinator: Mario Portanova - Production: Eleonora Bianchini - Investigation: Eleonora Bianchini, Martina Castigliani, Giuseppe Pipitone, Mario Portanova, Irpi (Investigative Reporting Project Italy) - Video: Franz Baraggino e Alessandro Sarcinelli - Art director: Pierpaolo Balani - Developer: Gianluca Buoncompagni

It does not stop at the 'Ndrangheta, Camorra, and Cosa Nostra. In the European Union's 28 Member States, about five thousand organized crime groups are under investigation according to the Europol 2017 report. Of course, few of these are as deep as the Italian mafias, under 145 investigations on a European level, coordinated by Eurojust from 2012 to 2016. Seven out of ten of these operate in more than one country, and they split an illegal market, including drugs and counterfeiting, which Transcrime estimates at almost 110 billion euro, about 1% of EU GDP. Investigations and reports highlight the importance of Russian-speaking and Turkish mafias, the rise of Albanian clan bosses in marijuana trafficking and other areas, the danger of lesser-known groups at an international level, biker gangs spreading in Northern Europe, and Vietnamese clans active mainly in Eastern Europe. No country can consider itself immune, as our interactive map shows. This even goes for even countries with excellent civic traditions and levels of crime decidedly under control, as the case of the Syrian mafia in Sweden shows.

Many of these organizations pollute the legal economy by laundering their profits and ultimately affect the economic and social life of parts of the country, just like the Italian mafias, though usually on a smaller scale. Yet, the system for fighting organized crime at an EU level seems to be mainly spinning its wheels, despite some progress made. For at least a decade, the Parliament in Strasbourg has been approving documents that ask specifically to extend the offense of mafia association to all Member States, the law, called 416 bis in the Italian penal code, and to allow unexplained assets to be confiscated, even without a criminal conviction, and is another cutting-edge "invention" of Italian legislation. But these documents have all remained dead in the water due to the opposition of several Member States, despite constant requests from Europol and Eurojust, which are the EU's police and court, respectively. Likewise, negotiations in the European Public Prosecutor's office have run aground, also because not wanted by several Member States.

Mafias and criminal organizations end up going "jurisdictional shopping", meaning that they take advantage of countries where standards (and investigations) are softer. Though there is less killing, the danger that investigators stress is their adverse effect on the economy, the market, and free competition. Europol observed in its 2013 report on Italian organized crime, "the overall strategy of Italian Mafias when operating abroad is that of keeping a low profile." The type of control sought by the Mafias when abroad is purely economic, in the wider sense, not limited to the essential goal of making money, but extended to all aspects of the production and consumption of goods and services, the backbone of any country." Consider, for instance, the burden on the economy of the huge profits made even by drug trafficking alone. As the Italian National Anti-Mafia Directorate wrote in its the 2016 report, "We must stop our generation and, more importantly, future generations, from ending up living in societies in which the free economy is undermined by the criminal economy."

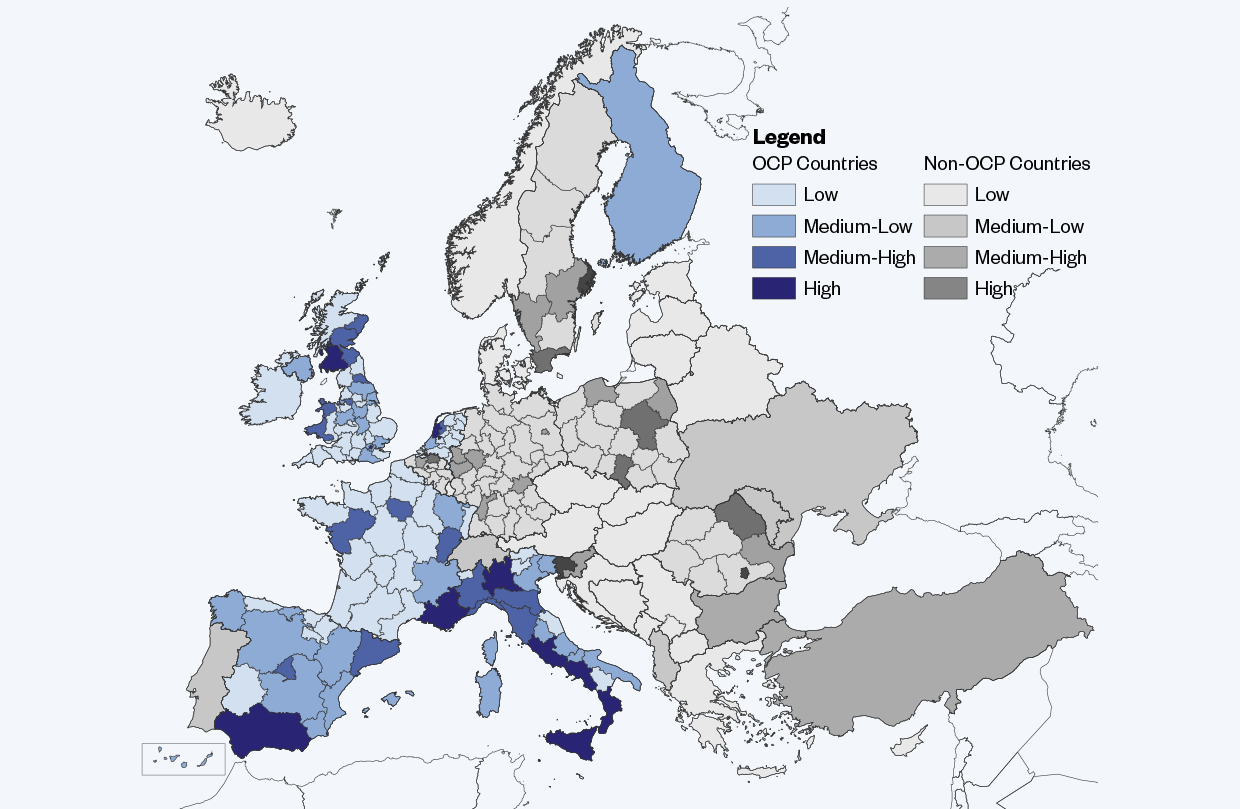

REGIONS WITH EVIDENCE OF ORGANISED CRIME INVESTIMENTS (OCP-TRANSCRIME)

CRIMINAL GROUPS IN EUROPE

We cannot assume that there are any corners of Europe immune from the mafia risk. Consider, for instance, that in 2004 the Camorra boss, Vincenzo Mazzarella, accused of mafia association and laundering, was caught by surprise and arrested at Eurodisney, outside of Paris, amidst furry mascots and pastel-colored hotels. For that matter, even in the mid-1980s, the Ndrangheta's Giacomo Lauro was trafficking cocaine in Netherlands, where he was arrested in 1992. An investigator told ilfattoquotidiano.it that Italian Anti-Mafia Investigation Directorate estimated that Calabrian organized crime had representatives in twenty European countries at that time. In Germany, two years after the Duisburg killings of August 2007, the German police managed to record the exact details of a 'Ndrangheta local meeting in Singen, Baden-Württemberg, which included old ritualistic formulas: "With irons and chains I baptize ...". The Netherlands was much upset by the recent discovery of the mafia involvement – again the 'Ndrangheta — in the flower market, a historic point of national pride. While Italian organizations can unquestionably be labeled "mafia associations," a term that Italian law invented for them, many other organizations operate in the 28 Member States have similar traits, such as the power of intimidation over those not involved in criminal activity and conditioning the economy and politics (the French police director Jean-François Gayraud, in his 2005 book Le Monde des mafias, Géopolitique du crime organisé, names as such the Sicilian Cosa Nostra, the American Cosa Nostra , 'Ndrangheta, Camorra, Sacra Corona Unita, Chinese Triads, Japanese Yakuza, and Albanian, Kosovar and Turkish crime organizations. But this is still debated among scholars). Europol's 2009 report distinguished as particularly dangerous groups those "able to interfere in the repression of law enforcement and its processes through corruption," concluding that such clans were found at the time in "Ireland, the UK," and to a greater extent in "the Czech Republic, Latvia, Lithuania, Romania, Bulgaria, Slovakia and, to a lesser extent, Hungary and Poland."

Definitions aside, if we look through European investigative reports and those of individual national police, we see several mafia-type groups, often able to operate between EU countries. Biker gangs in Northern Europe, such as the Hells Angels and Bandidos in Finland, have a real-life ability to intimidate and affect the legitimate economy (they share with the Italian mafia having both a public face and a hidden one). Many investigators with whom ilfattoquotidiano.it spoke for this investigative report mentioned the rise of Albanian clans, who are situating their pawns in several Member States to make the jump from marijuana trafficking to cocaine and heroin. Russian mafias are reported as active from Eastern Europe to the United Kingdom, especially in laundering. In Estonia, we are waiting to see how the criminal system develops after the 2015 assassination of the top boss of the Obtshak ("Common Fund"), Nikolai Tarankov, with a past in the Soviet KGB. Even Sweden woke up to discover in 2010, following a double murder, that the power of the Syrian mafia had reached some parts of the country, previously unbeknownst to all. Vietnamese crime is also making headways in Eastern Europe as it can profitably trade drugs and illegal migrants (to find out more about the situation in each of the 28 Member States, see the interactive map above).

CANNABIS INDOOR CULTIVATION (EUROPOL)

ITALIAN MAFIAS EXPORT

David Ellero, the officer of the military police responsible for the fight against crime organized for Europol, explains to ilfattoquotidiano.it "The Italian mafias are the only ones that started in the European Union. They know no boundaries, especially the 'Ndrangheta and Camorra, which are sometimes active in the same areas, but operate in different ways. The 'Ndrangheta tends to colonize an area and the Camorra merely forms points of contact for traffic and investments. These strategies differ little from those that led to mafia expansion in northern Italy. But we see much less Cosa Nostra in EU countries." Mafias do not spread at random; they tend to follow specific directions informed by opportunities for traffic and profit. "The main expansion reasons are drug trafficking and laundering," says Ellero. "One of the first directions is the Iberian Peninsula, which is a drug-trafficking hub. The second direction is Germany-Belgium-Netherlands because of the ports of Rotterdam and Antwerp. He continues, "Several thousand containers come there daily, so it is impossible to intercept cocaine loads without specific tips. The Netherlands, with Schipol Airport, its excellent freeways, and position in the center of Europe, is logistically perfect for trafficking. " Italian mafias are not the only ones: "There are several crime groups in the United Kingdom and major problems are emerging with clans of Albanians, Russians, Nigerians, and Turks. "Our mafias" are there but they keep a low profile and local authorities don't consider them a problem. And then there is the laundering issue. According to Transparency, 75% of luxury real estate in London is owned by companies based abroad." And there are black holes, like Eastern European countries where "we can't objectively know how Italian mafias are operating, though there are certainly investments there."

The danger for Europe, however, is not drugs, but laundering, which "pollutes the legal economy," Ellero continues. "Italian mafias have specialists for cleaning up dirty money abroad. Sometimes the same people who were selling drugs and committing murders 30 years ago now run restaurants." This is the origin of the low profile that can fool those who think that signs of a mafia presence in the 2000s were murders and bombs in shops. "The Dutch flower market investigation involved Calabrians who had been there for twenty years and no one had noticed a thing, including the local police."

"To find the mafias in the EU you have to follow the cocaine trail," a senior DIA analyst, agrees. The issue is often not countries but specific regions of them: "In Spain, the Costa Brava and the Costa del Sol have developed full-fledged clan logistics, becoming shelters for fugitives. Laundering by making local investments follows. Something similar happens in France in the Cote D'Azur," he continues. "And the ports of Rotterdam, the Netherlands, and Antwerp, Belgium, are the main access points for drugs from South America". There is the law of the market beyond that of crime. Bosses and their white collar criminals make their way to the most convenient locations: "Germany and Switzerland because they are rich; the former Yugoslavia because several checks are skipped partly because of widespread corruption among local law enforcement."

Can mafias really transplant themselves into areas that are apparently so different from their native ones? The experience of Northern Italy is a lesson for us, as we read in the essay, La Questione delle Mafie Italiane all'Estero: un'Agenda di Ricerca (“The Italian Mafias Abroad Issue: a Research Agenda”) by Joselle Dagnes, Davide Donatiello, Rocco Sciarrone and Luca Storti of the Department of Culture, Politics and Society at the University of Turin. The researchers say there are three basic paths of clan migration. The first is that of fugitives, who generally can not merely run as far as possible, but need special local "services," as we have seen in France and Germany. The second route follows that of trafficking, primarily of drugs, as has happened in Spain and the Netherlands, and in Eastern Europe. Third there is the possibility of investment in the legal economy, preferably where there are "business-financial professional competencies, often straddling the legal and illegal." This is the case in Switzerland, a country where courts often end up when following mafia money.

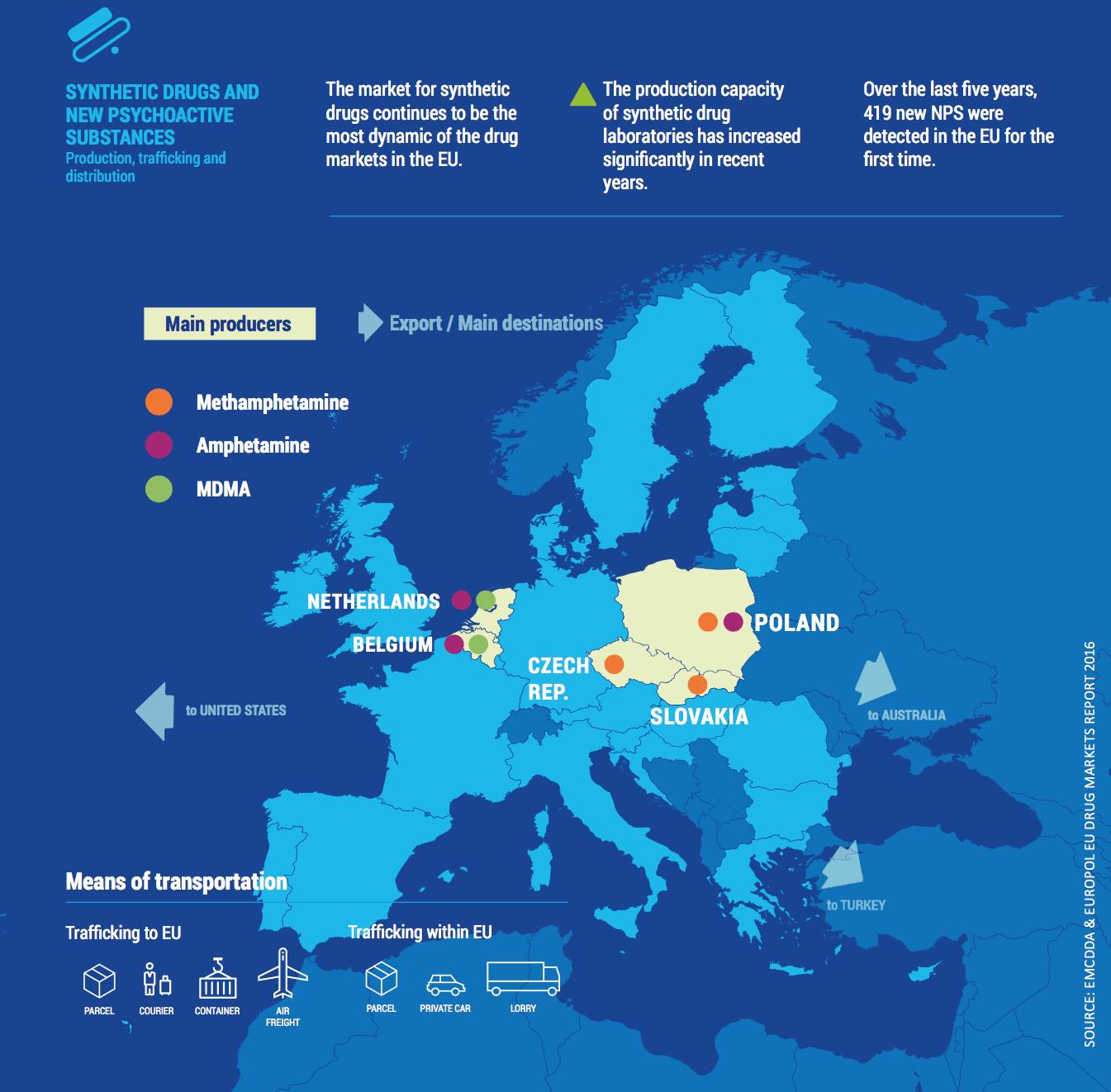

UNITED MAFIAS OF EUROPE

Of the five thousand criminal organizations under investigation in Europe, seven out of ten operate in several countries, and almost half, 45%, in several criminal areas, according to Europol in its Serious and Organized Crime Threat Assessment (SOCTA) 2017 report. Their members have 180 different nationalities, though 60% are native European. The drug market is still the largest illicit market in the Union, focused on by a third of the groups, for a value estimated at €24 billion a year. Though heroin, cocaine, and — in part — cannabis are produced outside EU borders, synthetic drugs are mainly locally made and, in fact, exported to the rest of the world, also according to Europol. As you can see from our map, the Czech Republic is the main producer in Europe of methamphetamine, in which Vietnamese organized crime plays a prominent role. In 2014, the Fuelco operation led to the seizure of a half ton of cocaine that came from Brazil by air, and arrested about 200 couriers. Twelve EU countries were involved, including Austria, Bulgaria, France , Germany, Sweden, and the United Kingdom.

SYNTHETIC DRUGS: PRODUCTION, TRAFFICKING AND CULTIVATION (EUROPOL)

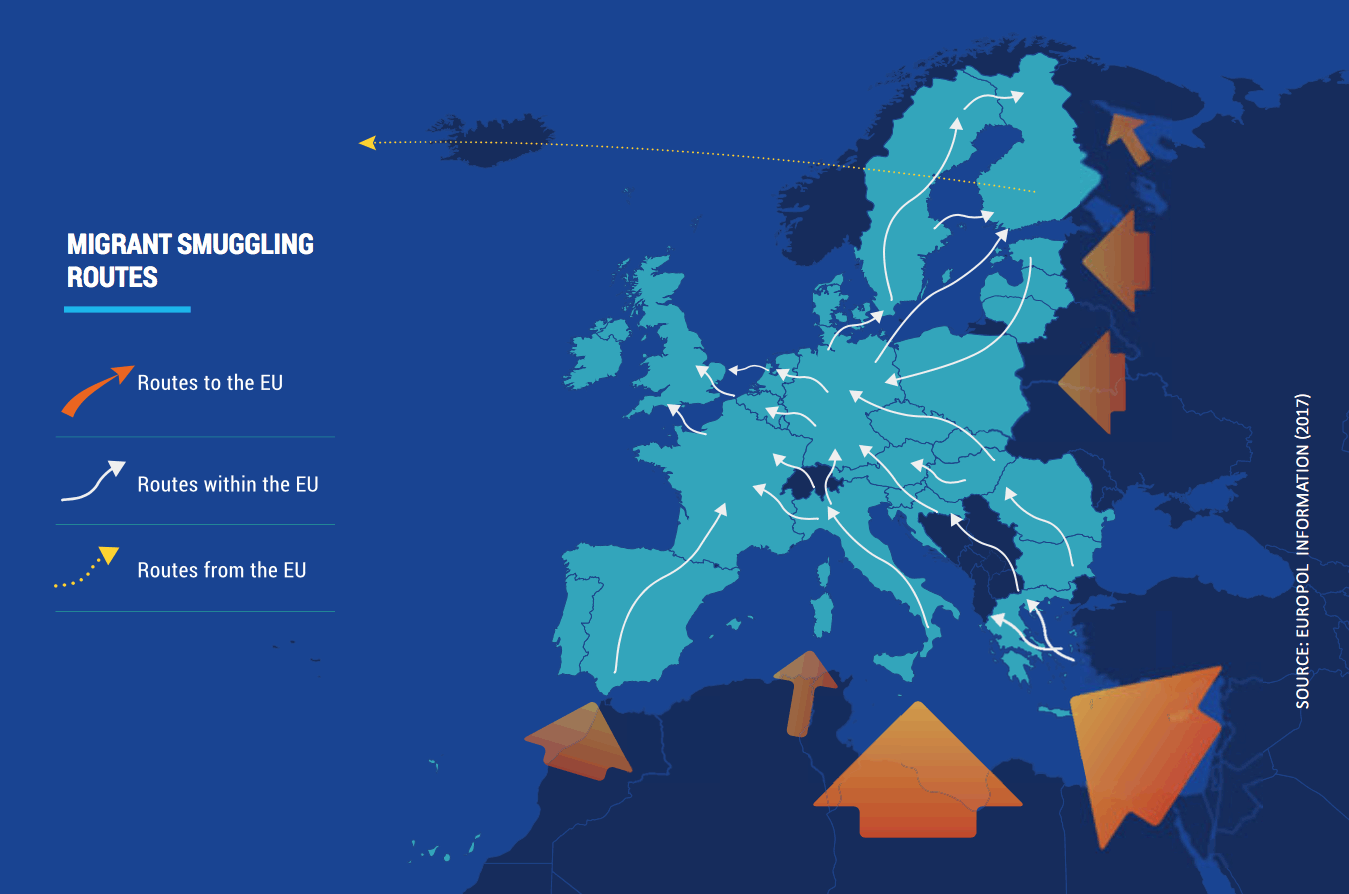

While drugs make up the lion share, there is emerging trade in trafficking in migrants and other humans for work exploitation, for sexual exploitation in bars and brothels, as shown by a survey of Chinese crime in Austria 2016. Of the more than one and a half million illegal migrants who came to the European Union in 2015 and 2016, by land or by sea, "almost all" paid a criminal organization, European police analysts note. Another thriving black market is counterfeiting, which involves frequent alliances between the Camorra and Chinese groups. It goes beyond dresses and purses. The 2016 Eurojust report mentions an investigation into counterfeiting machines. For example, Camorra affiliates bought a generator made in China for 35 euros. In Naples, they labeled it with a famous brand and resold it for 400 euros, as opposed to 1250 euros for the original. Such products, including dangerous equipment like electric saws and drills, did not respect European safety standards but were sold in twenty European countries. The investigation put 67 people in prison and allowed for the seizure of assets of 11 million euros.

POLLUTED ECONOMY

Major profits from large-scale illegal activities have to be laundered to enter the clean economy. This is increasingly done by external specialized groups, which take 5–8% for the service, Europol says. The sums involved are enormous. Consider that just one Chinese criminal group active in human trafficking, uncovered in Spain by the Snake 3 investigation, "laundered over 340 million euros from 2009 to 2015." In that case, the money tended to go to China, but a lot of laundered money is a burden on the real economy, in the form of businesses that distort free competition. Considering only the Italian mafias, the Eurojust 2016 report notes the infiltration into the legitimate economy in "Spain (particularly favored by the Italian Camorra), the Netherlands, Romania, France, Germany, and the UK." How does it happen? Primarily through "real estate investments and participation in public or private contracts, particularly in the field of construction, public utilities and waste disposal." The Transcrime Organized Crime Portfolio (OCP), edited by Ernesto Savona and Michele Riccardi, notes "cases of organized crime investments were found in almost all EU MS (24 out of 28)", predominantly in Italy, France, Spain, the United Kingdom, the Netherlands, Germany, and Romania. Dirty money, the OCP study says, is mostly "in areas with a historically strong presence of organised crime groups (e.g. southern Italy), in border regions, or in areas which may play a crucial role in illicit trafficking (e.g. Andalusia, or Rotterdam and Marseille with their harbors), large urban areas (e.g. London, Amsterdam, Madrid, Berlin) and tourist or coastal areas (e.g. Côte d’Azur, Murcia, Malaga or European capitals). Southern Spain, for example, attracts both the dirty money of Italian mafias, Russian criminals and northern European biker gangs. In recent years, criminal investments focused on "renewable energy, waste collection and management, money transfer, casinos, VLT, slot machines, games and betting".

WHAT HAS EUROPE DONE?

Europe in the 2000s, in some ways, seems to have much in common with post-war Italy, incapable of taking serious measures against mafia bosses and their underlings. This was also true in Italy at least until the early 80s, when they started to make their presence felt with massacres and "high-up" murders of governmental figures: politicians, judges, policemen, military police, and public officers who did not fold to the mafia gangs. Though a few steps forward have been made in recent years, as experts have recognized, on at least two crucial issues, we are spinning our wheels: first, extending the crime of mafia association, now only in effect in Italy with article 416 bis of the penal code, and, second, the ability to confiscate the assets from organized crime even without a final conviction, when serious signs of guilt are paired with the investigated party or defendant's failure to prove a legitimate source of assets. Recommendations on these issues have been made repeatedly to the Member States and the European Commission through resolutions, reports, and policies approved by the European Parliament in Strasbourg, but they all have yet to be enacted. Among those asking that these measures be taken are Eurojust and Europol, the highest judicial and investigative bodies of the European Union, those who are well aware of the mafia risk in countries that are still largely heedless.

Let us start by defining organized crime according to the European Union. The Council Framework Decision of October 24, 2008 (2008/841/JHA), based on the 2000 UN Convention against Transnational Organized Crime, defines it as such:"a structured association, established over a period of time, of more than two persons acting in concert with a view to committing offenses" punishable by at least four years deprivation of liberty, "to obtain, directly or indirectly, a financial or other material benefit." This definition, however, does not satisfy the Europol investigators because, according to the Socta 2017 report, it "does not adequately describe the complex and flexible nature of modern organized crime networks." Article 2 of the Framework Decision requires all Member States to consider the offense of organized crime itself as separate from the actual committing of a crime (it suffices to agree to commit or plan for illicit activity). Ten years later, this issue is still on the table. Eurojust's 2016 report notes that "not all Member States, however, have adopted similar provisions," and "when they have done so, the extent of the application of and penalties attached to such offenses varies greatly, and so do the possibility and requirements for applying special investigative techniques such as wiretappings." Denmark and Sweden still have no organized crime law. Individual crimes that have been committed are punished with the aggravating factor of colluding with several people. Germany and the Netherlands have legislation considered rather lenient. Bulgaria is one of the countries that harmonized its own legislation with the 2008 Framework Decision.

WHEN BORDERS STOP INVESTIGATIONS

This is the first problem faced when fighting the mafia on a European scale. The twenty-eight Member States do not even agree on what organized crime is, and in some cases, whether there is a need for such a crime. And then there is the fact that the specific offense of mafia association, which was an Italian invention (Article 416 bis of the Criminal Code, which dates back to 1982), does not exist elsewhere. For example, an investigation into the 'Ndrangheta group that starts in Reggio Calabria risks running aground in the Netherlands. For this reason, the European Parliament's 2011 resolution, voted on October 25, asked that all individual Member States "make associating with mafias or other criminal rings a punishable crime," and that they do so "even without any specific acts of violence or threats." This specification responds to mafias' ability to camouflage themselves as they have considerably declined their rate of violence, in Italy and abroad, to avoid drawing too much attention from investigators and public opinion. Six years later, no country has followed up on this request. The resistance to it was so strong that it disappeared from the final report of September 26, 2013, by the Special Commission on Organized Crime, Corruption and Money Laundering (CRIM), chaired by the Italian MEP Sonia Alfano (daughter of Beppe Alfano, the journalist that Cosa Nostra assassinated in Sicily in 1993). It was, however, in the draft dated June 10, 2013.

In 2013 as well, Europol called for a European "416 Bis”: in a report on Italian organized crime, writing: "Being a member of a Mafia-type organization must be considered as a crime per se." Anti-mafia legislation must be harmonized at EU level, and extradition requests for fugitive Mafiosi should be prioritized by receiving competent authorities." No progress has been made since. The "Europolice" to the "Eurojudges," in Eurojust's 2016 report: "Experience shows that the existence of different legal definitions and the lack of an equivalent to Article 416 bis of the Italian Criminal Code cause major legal and operational obstacles to effective judicial cooperation. Moreover, in many European legal cultures, there is not even mandatory prosecution, a pillar of the Italian system alongside the independence of the judiciary from political power.

MIGRANT SMUGGLING ROUTES (EUROPOL)

CONFISCATION WITHOUT CONVICTION

If we cannot pursue mafia members throughout Europe until we catch them committing another type of crime, the other option is to hit them in their wallets. The cornerstone of the fight against organized crime is undoubtedly the Directive on the freezing and confiscation of instrumentalities and proceeds of crime in the European Union of April 3, 2014 (2014/42/EU). Hailed as a breakthrough, the legislation once again ended up being watered down during the approval procedure. The final text is based on recognizing that, though cross-border criminals definitely aim for profit, "the existing regimes for extended confiscation and for the mutual recognition of freezing and confiscation orders are not fully effective." The problem is specifically "differences between Member States’ law." Not all countries considered this a problem. The United Kingdom and Denmark pulled out, did not sign the directive, and are not bound by it. Poland voted against it; Ireland voted for it but limited to the crimes covered by its own law.

And this text was far from revolutionary or reactionary. It merely says that all Member States shall take the necessary measures to enable them to "confiscate, either in whole or in part, instrumentalities and proceeds" of crime, though only "subject to a final conviction for a criminal offense" (with the exception if the defendant is too ill to stand trial or is a fugitive). On the face of it, this might seem obvious; taking money or wealth from someone is a serious measure, affecting property rights, so it can only be applied to those found guilty without possible appeal. But the reality is quite different. In Italy, which, for obvious reasons, has the most advanced anti-mafia regulations, assets can be permanently confiscated by the State, even without a final conviction. And, indeed, even if they are acquitted. This is because for suspects of particularly serious offenses, there is a "reversal of the burden of proof"; if the suspect fails to demonstrate that his or her money and assets are legitimate and verifiable, the State can remove them. This is regardless of whether there is a later conviction or acquittal in the criminal court. This preventive measure, also introduced in 1982, is a cornerstone of Italian anti-mafia legislation. Law 646 was named for Pio La Torre, a PCI parliamentary member that Cosa Nostra killed that same year in Palermo.

A MISSED OPPORTUNITY?

But Europe chose to stop short. When the directive was approved, Sonia Alfano, former President of the CRM Commission, gave voice to the disappointment of the Italian anti-mafia front, accusing "those Member States who prefer to protect defendants rather than victims of crimes." Countries like Germany, champions of austerity, who, when "given the chance to return assets gained from illicit activities to the European Union's coffers, blocked the way and obstructed approval of a more effective, ambitious text." During discussion about the confiscation directive, amendments were introduced by the Committee for Civil Liberties, Justice and Internal Affairs of the European Parliament clearly stated that an effective fight against organized crime would unquestionably need measures separate from criminal convictions, especially regarding "assets and profits." Essentially the same request was made in many documents approved in Strasbourg over the years, from the 2011 resolution to Alfano's 2013 report. In 2013 as well, in the Europol report on Italian mafias, the need was seen for "new and more effective provisions...to realize...extended confiscation and non-conviction based confiscation," making use of civil law, "whereby the burden of providing evidential proof is lessened."

Why did these intentions fall by the wayside? Leading opponents of confiscation without conviction included the Council of Europe, with Finland in particular, and the Committee of the Regions. This was explained by a study by the Icarus Project, coordinated by Nando dalla Chiesa of the University of Milan and by Anna Catasta of the European Initiative Centre, financed by the European Union and released in 2016: "The opposition was due primarily to the fear that preventive confiscation would be a disproportionate risk on the issue of the protection of the rights of property." Countries with the most experience with organized crime were the ones that pushed for more extensive confiscation, such as Ireland which introduced it in its 1996 regulation to fight the rise of local gangs. Spain and Croatia, in addition to Ireland and Italy, established aggravating circumstances that could lead to confiscation without conviction. These include mafia (for Italy) and organized crime (for other countries).

In its 2016 report, the National Anti-Mafia Directorate agreed that this was a missed opportunity. The Directorate emphasized, on the subject of the directive's limitations, the "need to untie the asset confiscation measure from a conviction for a certain crime and allow it to be applied in cases of a verified illicit origin of assets coming from the person's criminal activity." This should be done "even in cases where there the proof requirements for a criminal conviction have not been met, or in cases of flight, death, and immunity from prosecution." The judges of the "super-prosecution" led by Franco Roberti objected to the "theoretical legal questions whose main effect is to discourage any initiative on the topic", while, in the absence of harmonic laws, there has been a growin number of approvals for the seizure and confiscation of assets coming to Italy from other Member States to Italy thanks to international letters rogatory. Letters rogatory are currently in effect with France (6), Netherlands (2), Spain (2), Luxembourg (3), Ireland (2), Austria (1), and the United Kingdom (3). Legal cooperation seeks to make up for the shortcomings of national legislation. The DNA also emphasized the tendency of legal officers of European States to ensure the "execution of sequestering and confiscation measures provided by another State."

ITALY: BILLIONS EURO REGAINED

In a certain sense, the judicial machine propels itself forward. So why does Europe insist on not creating a clear, efficient system for attacking large criminal assets, as the judge Giovanni Falcone showed us? Why forgo a measure that criminals fear more than prison, as many wiretaps by Italian investigations showed? Why forgo taking in significant sums of money, part of which can be returned to the community, as happen sin Italy with confiscated assets given to public agencies and associations, or used to build barracks for military police or do volunteer work in mafia-dominated areas? Just one of many examples: on April 3, 2013, the Anti-mafia Investigative Directorate of Palermo confiscated some 1.3 billion euros from Vito Nicastri, a wind energy businessman in Alcamo (Trapani), accused, among other crimes, of being a cover for the last major Cosa Nostra fugitive, Matteo Messina Denaro. The mega-confiscation was upheld two years later by the Court of Appeal even in the absence of a mafia conviction against the businessman. This was, to be certain, a record amount, but such confiscations for tens and hundreds of millions of euros against mafiosi and white-collar crimes are commonplace in Italy. Between 1992 and 2016, the DIA seized 21,3 billion euro (15,2 without conviction) and confiscated 8,5 billion (7,6 without conviction). This is a treasure trove, especially in times of depleted public coffers.

At top European institutions, there appears to be an endless struggle between protecting rights and pursuing justice, and they are three decades behind Italian debate on the issue. Moreover, confiscation without conviction has been given the green light many times by the European Court of Human Rights, as judge Francesco Menditto has noted in his numerous studies. Judges have clarified that this is not punishment without trial, but a matter of preventive measures. It is also completely proportional as the "inordinate profit that mafia-style associations derive from their illicit activities, giving them power that undermines the supremacy of State law." This is why "the means adopted to combat this economic power, particularly the confiscation measure complained of, may appear essential for the successful prosecution of the battle against the organization in question" (ECHR January 5, 2010, Bongiorno and others v. Italy). Confiscation without conviction is not, moreover, peculiar to a country where thousands have died because of mafias, including about a thousand "innocent people," according to Libera's estimates, which memorializes the victims on the day dedicated to their memory by naming them one by one. Menditto notes that "in the United States, an initial demonstration by the prosecution of 'probable cause' is enough to shift the burden of proof on the defense, which has to offer proof that the assets are unrelated to crime dynamics.". Various types of confiscation without conviction are already provided for in several Member States, mentioned in the Icaro study, including Austria, the United Kingdom, Ireland, Bulgaria, and Slovakia, in addition to Italy. And precisely like a "416 bis" for everyone, the European Parliament itself, in the resolution of 2011, invoked it as a measure that would "make it more difficult for [criminals] to hide their assets." But this was in vain. And, as such, "Italian judges will be forced to continue following convoluted and uncertain paths of cooperation with Member States ' counterparts, on each occasion relying on the sensibility of a foreign court that varies widely from country to country," wrote the Italian Anti-Mafia Parliamentary Committee, chaired by Rosy Bindi, in the report on confiscated assets of April 9, 2014 as a freshly-approved directive on confiscation.

Though the European system for fighting crime is making small steps forward, it seems to be going around in circles on the most sensitive aspects. On October 7, 2016, the European Parliament approved the report on the fight against corruption, prepared by MEP Laura Ferrara, which partially adopts the work of Alfano's commission. The report's 35 pages echoes once again the same wish list to the Commission, that the offense of "criminal association regardless of consummation of criminal ends" be punishable, specific legislation on "a particular type of criminal organization whose members use the power of intimidation deriving from the bonds of membership, the state of subjugation and conspiracy of silence" (in practice, the 416 bis of the Italian code), "confiscation without conviction." It is like a broken record.

POLITICS AND THE "ITALIAN QUESTION.

Italian history shows that the most stringent and effective anti-mafia measures have been taken in the wake of serious bloodshed, such as the assassinations in 1982 in Palermo of the prefect Carlo Alberto dalla Chiesa, and the PCI Deputy Pio La Torre. For instance, the 'Ndrangheta killings in Duisburg of 2007 temporarily ignited discussion on the expansion of the Italian mafias in Europe. When there is no bloodshed, there is waning attention on the fight against the mafia (although it usually is during pax mafiosa periods that clans are consolidated and attack the clean economy). The European case is proof. The most expert alarms raised fell on deaf ears. On March 30, 2011, Roberto Scarpinato, the judge of Palermo who is among the most astute observers of the phenomenon, told Strasbourg, "In the heart of Europe, the mafia's money laundering is constantly growing in a wide variety of industries and the risk of a hidden mafia-economic colonization in growing areas of Europe cannot be underestimated." "The lesson that we can take from the spread of the mafias in the north of Italy, which had been thought immune, is a wake-up call that is sounding for all of Europe, not just Italy. Building progressive EU criminal legislation against transnational organized crime that includes a homogeneous field of offenses, investigation and confiscation tools is an essential medium-term objective." But, as we have seen, the European Parliament, the European Union's directly elected highest legislative body, addresses the mafia only with enormous difficulty. The reasons for this are legal, political, and more. Consider that Brussels has had a relatively recent experience of fighting mafia-type criminal organizations. The CRIM Commission had an Italian President (Sonia Alfano) and two Vice-Presidents (Rosario Crocetta and Salvatore Iacolino); it was basically seen as a Commission created by the Italian Parliament for Italian problems.

"The accusation has been made that only we Italian MEPs are talking about mafias in Europe, as if it were only our fixation," Laura Ferrara, MEP of the 5-Star Movement told ilfattoquotidiano.it. "It will probably take time for other countries to realize that the mafia is a problem in Europe and outside of Europe too". The connection between the mafias and Italy has a lot in common with the connection between terrorism and Spain. This point was made by Juan Fernando López Aguilar, former Justice Minister José Zapatero and MEP of the Socialist Party. He says, "When Spain had a terrorism problem, we asked for help from other EU Member States. On several occasions, we discussed with them strategies to adopt to fight it. But many countries, like Luxembourg or Finland, had never had any direct experience with it, and considered themselves quite apart from us; it seemed as if terrorism were only our problem. Now, it is clear that it is a threat to everyone, and the Spanish experience has become critical for the entire European Union. And now the exact same thing is happening with mafia-type crime".

THE LEGAL HURDLES

But political and social differences aside, we have seen how the European fight against the mafia has technical and legal difficulties tied to the difference between criminal codes. "The main objective is to work on more coordination between investigative authorities. Unfortunately, as we all know, this comes up against resistance from certain legal systems and legal cultures," explains Elly Schlein, Italian MEP elected with the Democratic Party, co-President of Integrity, Transparency, Corruption and Organized Crime (ITCO). She says, "In October, we passed a follow-up to the 2012 CRIM resolution. This was an important step; Parliament asked for a definition at a European level of the crime of mafia association and related illegal conduct". During the process, the parliamentary members from the Netherlands once again set themselves against it. Ferrara, the Italian MEP, explains, "We faced strong resistance from our Dutch colleagues who kept on trying to present amendments to remove the reference to mafia association." And it is the Netherlands that has the other president of the intergroup on organized crime, Dennis De Jong of the Socialist Party, who refused an interview with ilfattoquotiano.it. Why? "Our party has always been very critical about introducing new legislation at a European level to combat organized crime," is the answer given by the staff of the Dutch MEP to our request to meet him in Brussels. It would have been extremely useful to interview De Jong to understand the reasons for his position, but his office also rejected our second email request. "Unfortunately, Mr. de Jong does not have time for a short interview. We are sorry, but considering his busy schedule, we must give priority to meetings with the Dutch media, which bring news to our constituents."

Schlein explains, "Unfortunately, many colleagues fail to see how the mafias are spreading throughout the European Union; they do not have this awareness." "And as long as we fail to harmonize the means for fighting it, we are unlikely to combat it effectively above the national level." The key concept is the harmonization of legal systems, ensuring that different jurisprudential doctrines find common ground, something of a legislative safe haven where special legislation can be applied to combat mafias. Lopez Aguilar says, "This was already provided for in the Treaty of Lisbon, which marked the origin of European criminal law. It is just a matter of applying it and making its contents meaningful. We just need to respect the political promise that was made," says Lopez Aguilar. Ferrara considers it more complex. She explains, "In Europe, we are dealing with twenty-seven different legal traditions. For example, though the Italian system works through mandatory prosecution, other Member States follow priorities set by the government each year." She continues, "If fighting organized crime is not among those priorities, when a request is made, as an example, by Italy to the Netherlands, to work together on a particular investigation, they might not act on it because they don't deem it a priority." Where is the risk? The Italian parliamentarians we interviewed agree. "Mafias are currently making better use of the advantages guaranteed by the freedom of movement in the European Union than private citizens manage to do. They exploit "loopholes" to go commit crimes where they know that they cannot be prosecuted. " This is what we discussed above, "court shopping." As such, without clear, unified legislation, Europe risks becoming a haven for mafias from all over the world.

WHAT DO INVESTIGATORS SAY?

But some are skeptical about the penal approach of "416 bis for everyone," such as professor Ernesto Savona, Director of Transcrime, the interuniversity center that has produced innovative, in-depth studies on mafia investment in Europe. This is precisely where he thinks we ought to focus. He tells ilfattoquotidiano.it, "This is a move towards more 'limited', flexible mafias, with fewer murders and more money moving around." In this situation, "There is no use insisting on asking for a unified anti-mafia legislation; even the anti-mafia Commission of the European Parliament produced nothing. I'd rather get a chance at international confiscation that really works. " Everything else can be done with "more cooperation between national police and more training. We need to cut the ties between dirty and clean capital," Savona concludes. Regarding investigative cooperation, the European Public Prosecutor's Office is on its way to becoming the third major failure in the fight against mafias on the European level. The 2015 report by the Italian Anti-Mafia Directorate emphasized that while co-ordination efforts between judicial offices were bearing fruit, the results of EU-based negotiations on that front had been "quite disappointing." Meanwhile, individual cooperation procedures are burdened by "excessive formalities and sometimes an unacceptable pace." DNA continues, "One reason is that some authorities still feel that mafia-type crime is just an Italian problem, and they underestimate its ability to operate at a transnational level." In its 2017 annual report, Eurojust emphasizes the difficulty of making use of effective tools like wiretapping when an inquiry crosses national borders, even if within the EU: "Different standards in national legislation remain a significant challenge in using telecommunication wiretaps, especially in terms of admissibility of evidence."

David Ellero, Europol director of combating organize crime, voices the dream of today's anti-mafia police: "When Messina's police hear of local criminal activities abroad, it should able to call the Duisburg station with the same ease with which it would call the Milan station." Ellero is an officer of the branch at The Hague, where the European police has its headquarters. Every day, he sees the consequences of the major European shortcomings in the fight against the mafia: "In Germany, if you buy a car in cash for €60,000, no one says anything. And my German colleague wants me to give him proof that that money came from crime." The "reversal of the burden of proof" does not apply in Berlin. Ellero continues, "This is an explosive mixture. In the Netherlands, if you call someone a mafioso, he can sue because that crime doesn't exist there. In some Member States, criminal records are actually erased after three years." We asked Ellero if, though legislative harmonization remains a mirage, if he had any news about mafia infiltrations in major European contracts. His answer is discouraging, "I don't know because I don't have the means to check it." It is a risk because "outside of Italy you can not ask for anti-mafia certification. If a mafioso opens up his company in Austria, you can't check it anymore." If Ellero could make a wish list of EU legislative measures, in addition to 416 bis and confiscations without condemnation, he would ask for a "package of regulations for excluding from bidding apparent mafia affiliates."

It is difficult to pursue mafiosi, let alone white collar criminals. "In Italy, we persecute professionals serving mafia organizations with outside pursuit, but abroad ...," the DIA senior analyst stops short and smiles, at the Rome headquarters of the inter-force group that Giovanni Falcone demanded. Money laundering investigations are smoother as European legislation on it is more uniform and consistent with the relevant directive (2015/849). The practice, however, is not uniform: "France and Spain 'trust' our measures," he explains, "because they come from the judicial authorities, are appealable and have been recognized by the European Court of Human Rights." On the other hand, "Opening an organized crime proceeding in Germany and France is not easy," Fabrizio Fantini explains, head of international relations at DIA. "Judges want proof given before approving the wiretaps. This makes it hard to investigate, for example, unexplained wealth, or a clan that is in the process of forming. That is why we insist on preventive measures, such as ensuring that no license is granted to dangerous persons. "As in Europe, borders exist only for judges and law enforcement; a license for online gambling obtained in Austria can be made valid throughout the EU because of free movement. Then, there are the loopholes: "The Netherlands Antilles are part of the Netherlands, but the European Arrest Warrant doesn't apply there. And the criminals know it." It's a short way from the Antilles to Cayman and then we come up against the issue of non-traceable financial assets. Fantini concludes, "Offshore accounts are central to the fight." "And with Brexit, who's to say that the UK won't become a tax haven?"