Bruxelles – A photo

Maggio 2012, uomo in fuga dalla guerra in Sud Sudan – Foto di Olivier Jobard

You might be leaving from London or Bujumbura, it wouldn’t change. Whatever the airport is, the gate for the flight to Brussels is unmistakable: all passengers are dressed the same way. They all have a Samsonite suitcase, Church’s shoes. A coat with a built-in down jacket. They are all dressed as government officials. All perfectly shaved, the women with a pearl necklace.

You can’t not notice them. Especially if the airport is the Athens airport, and you are coming from Greece, and in Greece you were coming from Turkey, and in Turkey you were coming from Iraq, and it’s been weeks, or perhaps years, that you have been on the road, or rather in the mud, in the sea, together with thousands of Syrians, Afghans, Iraqis.

They all have the eco-friendly cotton bag with the European Union logo. With the logo of the Unhcr, of the Wfp, the Iom, the Wwf, the most disparate initials, they all have been here for three days, and they are all here talking of how heartbreaking is what they’ve seen, how deeply they’ve been upset, upset forever, and where they are gonna go for the weekend. And honestly, I get an allergy attack. Why the hell are you coming to their rescue, if you are drowning them?

There’s no way. I can’t stay in Brussels for more than a day. Because I can’t see Brussels, actually. It disappears behind these dozens, hundreds of officials with their formal look: their overpaid lives so far away from the world they pretend to take care of. And I get an attack of sadness. And then of despondency, and then of intolerance, and after one day, honestly, I am tempted to throw a shoe at whoever I come across: because in the countries, in the wars I live in, I write from, what I am impressed by the most is not the brutality, the sheer ferocity, the extreme cases, no: what I am most impressed by, always, is the banality of evil. Be it Syria or Greece.

I am impressed by the accomplices, rather than the actual perpetrators. The indifference, the cowardice, the selfishness. The bureaucracy. I was still an undergrad student when I went to Kosovo for an internship at the Pristina office of the embassy of Italy in Beograd – Kosovo wasn’t a state, at the time. And at the time, like now, Albanians were all hunting for a Schengen visa. But directives were clear: to deny it. To anybody. To say No. Well, not even to say No. Our office was a two-storey building, and on alternate days, we worked downstairs or upstairs. To apply for a visa, Albanians had to call and get an appointment: when we were at the ground floor, yet, we said to call the number of the first floor, and when we were at the first floor we said to call the number of the ground floor. It could be a businessman, a PhD student, it could be a terminally ill. We had to say no. No to anybody. Or they would invade Italy. There was this old woman in her seventies, whose all sons had moved to Europe. And she wished to go to London to meet her new grandson. If she had not come back to Kosovo, an old woman in her seventies, and even if her sons had left her penniless in the street, such a small woman, barely a meter tall, a woman almost dead, how much she could weigh down the state budget? A salad per day? A chicken sliver, once in a while?

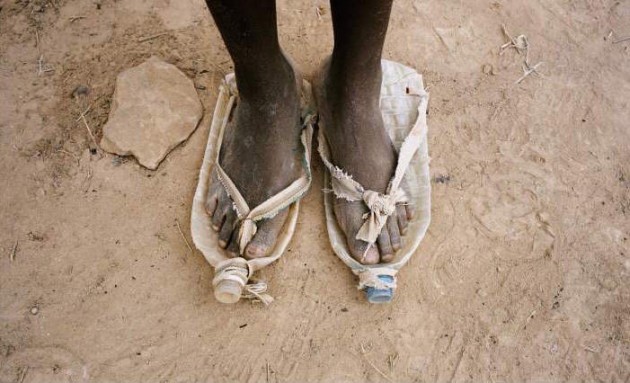

But in the end we were there, in our office. Nothing more. All dressed up. We were simply adding a stamp, a signature. We were simply handling administrative tasks. We were simply complying with the law. And yet as Luca Rastello said: many crimes are better than such a law. And you are always told: It’s for security reasons. It’s because of complex reasons, it’s because of the international balance of power, of the macroeconomic stability. It’s for reasons that you can’t grasp from outside. Truthfully: it’s because we want to have fifteen pairs of shoes while two thirds of human beings walk barefoot. It’s not complex at all. You hold five BAs and seven MAs, you are fluent in eight languages. It’s really so complex for you?

Because in the end it isn’t true that they don’t get it. And that’s also why I can’t stay in Brussels for more than a day. Because I was like that, too, until three years ago. It was my job. And so in the evening, when they hear that you come from another life, from their same life, they always invite you for dinner, and after three hours, three hours and three bottles of wine, gloomy, they always start confessing how pointless they feel. How useless. Or worse: complicit.

And yet nobody ever speaks out. Nobody ever quits. They talk with me for hours, in anguish. And I know that they expect some words of comfort. A justification, a mitigating circumstance. Anything. Something like: But I know you are different. But I know that you are here for changing the system from within. I know that in the end you’ll buy Unicef cards for Christmas.

Sorry. Those in need of words of comfort, in the world, are rather those who are now, right now, desperately waiting for you to answer the phone, instead of going to Greece to hand out life belts. I know you are not all the same, I know, I know some of you are amazing – but there’s no way. I can’t stay in Brussels for more than a day.